1. Taj Mahal or shiv temple tejo mahalaya 2. prahalad jani - The immortal 3. Ashoka's 9 unknown men 4. Cursed village of Kuldhara 5. Roopkund Lake 6. Death of subhash chandra bose - Gumnani Baba

This issue has been debated for long a petition a few years back in the Supreme Court too had been struck down after it was said that the Taj Mahal was originally a vedic temple.

P N Oak had written a book, Taj Mahal a true story in which he argues that it was a hindu temple. Let us understand what the entire issue is about and why many have said that the Taj Mahal in reality is Tejo Mahalay. Several sites have posted arguments on why the Taj Mahal was in reality a temple and not the tomb of Mumtaz, wife of Mughal ruler Shahjahan.

Taj Mahal or Tejo Mahalay

The term Tajmahal itself never occurs in any mogul court paper or chronicle even in Aurangzeb's time.

"Mahal"is never muslim because in none of the muslim countries around the world from Afghanistan to Algeria is there a building known as "Mahal".

The explanation of the term Tajmahal derives from Mumtaz Mahal, who is buried in it, is illogical- Her name was never Mumtaj Mahal but Mumtaz-ul-Zamani.

Several European visitors of Shahjahan's time allude to the building as Taj-e-Mahal is almost the correct tradition, age old Sanskrit name Tej-o-Mahalaya, signifying a Shiva temple.

The term Taj Mahal is a corrupt form of the sanskrit term TejoMahalay signifying a Shiva Temple. Agreshwar Mahadev i.e., The Lord of Agra was consecrated in it.

The tradition of removing the shoes before climbing the marble platform originates from pre Shahjahan times when the Taj was a Shiva Temple. Had the Taj originated as a tomb, shoes need not have to be removed because shoes are a necessity in a cemetery.

Visitors may notice that the base slab of the centotaph is the marble basement in plain white while its superstructure and the other three centotaphs on the two floors are covered with inlaid creeper designs. This indicates that the marble pedestal of the Shiva idol is still in place and Mumtaz's centotaphs are fake.

In India there are 12 Jyotirlingas i.e., the outstanding Shiva Temples. The Tejomahalaya alias The Tajmahal appears to be one of them known as Nagnatheshwar since its parapet is girdled with Naga, i.e., Cobra figures.

The famous Hindu treatise on architecture titled Vishwakarma Vastushastra mentions the 'Tej-Linga' amongst the Shivalingas i.e., the stone emblems of Lord Shiva, the Hindu deity. Such a Tej Linga was consecrated in the Taj Mahal, hence the term Taj Mahal alias Tejo Mahalaya.

Prahlad Jani, also known as Mataji or Chunriwala Mataji, (13 August 1929 ― 26 May 2020) was an Indian breatharian monk who claimed to have lived without food and water since 1940. He said that the goddess Amba sustained him. However, the findings of the investigations on him have been kept confidential and viewed with skepticism. He made several media and public appearances.

Biography[edit]

Prahlad Jani was born on 13 August 1929 in Charada village in British India (now in Mehsana district, Gujarat, India).[1] According to Jani, he left his home in Gujarat at the age of seven, and went to live in the jungle.[citation needed]

At the age of 12, Jani underwent a spiritual experience and became a follower of the Hindu goddess Amba. From that time, he chose to dress as a female devotee of Amba, wearing a red sari-like garment, jewellery and crimson flowers in his shoulder-length hair.[citation needed] Jani was commonly known as Mataji ("[a manifestation of] The Great Mother"). Jani believed that the Goddess provided him with water which dropped down through a hole in his palate, which allowed him to live without food or drink.[1]

Since the 1970s, Jani had lived as a hermit in a cave in the forest in Gujarat. He died on 26 May 2020 at his native Charada. He was given samadhi in his ashram at Gabbar Hill near Ambaji on 28 May 2020.[2][3]

Investigations[edit]

Two observational studies and one imaging study of Jani have been conducted. The observational studies were one in 2003 and one in 2010, both involving Dr. Sudhir Shah, a neurologist at the Sterling Hospitals in Ahmedabad, India, who had studied people claiming to have exceptional abilities, including other fasters such as Hira Ratan Manek. In both cases the investigators confirmed Jani's ability to survive healthily without food and water during the testing periods, although neither study was submitted to a scientific journal.[4] When questioned six days into the 2010 experiment, the DRDO spokesperson announced that the study's findings would be "confidential" until results were established.[5] Uninvolved doctors and other critics have questioned the validity of the studies[6][7] and stated their belief that, although people can survive for days without food or water, it is not possible to survive for years,[7] especially since glucose, a substrate critical to brain function, is not provided.[8]

2003 tests[edit]

In 2003, Dr. Sudhir Shah and other physicians at Sterling Hospitals, Ahmedabad, India observed Jani for 10 days. He stayed in a sealed room. Doctors said that he passed no urine or stool during the observation, but that urine appeared to form in the bladder.[1] A hospital spokesperson said that Jani was physically normal, but noted that a hole in the palate was an abnormal condition.[1] The fact that Jani's weight dropped slightly during the 10 days has cast some doubt on his claim to go indefinitely without food.[9]

2010 tests[edit]

From 22 April until 6 May 2010, Prahlad Jani was again observed and tested by Dr Sudhir Shah and a team of 35 researchers from the Indian Defence Institute of Physiology and Allied Sciences (DIPAS), as well as other organizations.[10][11][12] The director of DIPAS said that the results of the observations could "tremendously benefit mankind", as well as "soldiers, victims of calamities and astronauts", all of whom may have to survive without food or water for long durations.[13] The tests were again conducted at Sterling Hospitals.[14] Professor Anil Gupta of SRISTI,[15] involved in monitoring the tests, described the team as being "intrigued" by Jani's kriyas apparently allowing him to control his body's physiological functions.[16]

The team studied Jani with daily clinical examinations, blood tests, and scans. Round-the-clock surveillance was reportedly followed using multiple CCTV cameras and personal observation. The researchers say that Jani was taken out of the sealed room for tests and exposure to sun under continuous video recording.[17]

After fifteen days of observation during which he reportedly did not eat, drink or go to the toilet, all medical tests on Jani were reported as normal.[17] The doctors reported that although the amount of liquid in Jani's bladder fluctuated and that Jani appeared "able to generate urine in his bladder",[16] he did not pass urine. Based on Jani's reported levels of leptin and ghrelin, two appetite-related hormones, DRDO researchers posited that Jani may be demonstrating an extreme form of adaptation to starvation and water restriction.[18] DIPAS stated in 2010 that further studies were planned,[19][20] including investigations into how metabolic waste material is eliminated from Jani's body, from where he gets his energy for sustenance, and how he maintains his hydration status.[21]

2017 Brain Imaging Study[edit]

Independent of DRDO studies, IIT Madras team has conducted an imaging study in 2017. They have collected Jani's brain images and measured the size of Pineal and Pituitary glands. The result of the imaging study shows that the size of Jani's Pineal and Pituitary glands are of the same order of a 10 year old boy. The study results have been published in scientific journals.[22]

Reactions[edit]

Dr. Michael Van Rooyen, director of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, dismissed the observation results as "impossible", observing that the bodies of profoundly malnourished people quickly consume their own body's resources, resulting in renal/liver failure, tachycardia and heart strain. A spokeswoman for the American Dietetic Association stated that, "The bottom line is that even fasting for more than a day can be dangerous. You need food to function."[6] Nutrition researcher Peter Clifton also disagreed with study results, accusing the research team of "cheating" by allowing Jani to gargle and bathe, and stating that a human of average weight would die after "15 to 20 days" without water.[7] People who avoid food and water to emulate mystical figures often die.[7] Sanal Edamaruku characterized the experiment as a farce for allowing Jani to move out of the CCTV cameras' field of view, claiming that video footage showed Jani was allowed to receive devotees and to leave the sealed test room for sunbathing. Edamaruku also said that the gargling and bathing activities were insufficiently monitored. Edamaruku was denied access to the site where the tests were conducted in both 2003 and 2010,[4] and accuses Jani of having "influential protectors" responsible for denying him permission to inspect the project during its operation, despite having been invited to join the test during a live television broadcast.[4] The Indian Rationalist Association observed that individuals making similar claims in the past have been exposed as frauds.[citation needed] In 2010, the prominent scientific sceptic James Randi criticized the studies performed by the Indian government, citing insufficient scrutiny of the subject. He also proposed that if Prahlad Jani could prove his claims, he would receive the One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge prize.[23]

In September 2010, Dr. Shah announced that scientists from Austria and Germany had offered to visit India to carry out further research on Jani, and scientists from the United States had also offered to join the research. Jani has expressed interest in cooperating in further investigation.

3. Ashoka's 9 unknown men.

The Nine Unknown is a 1923 novel by Talbot Mundy. Originally serialised in Adventure magazine,[1] it concerns the Nine Unknown Men, a secret society founded by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka around 270 BC to preserve and develop knowledge that would be dangerous to humanity if it fell into the wrong hands. The nine unknown men were entrusted with guarding nine books of secret knowledge.

Plot[edit]

In the novel the nine men are the embodiment of good and face up against nine Kali worshippers, who sow confusion and masquerade as the true sages. The story surrounds a priest called Father Cyprian who is in possession of the books but who wants to destroy them out of Christian piety, and a number of other characters who are interested in learning their contents.

Influence[edit]

The concept of the "Nine Unknown Men" was further popularized by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier in their 1960 book The Morning of the Magicians. They claimed that the Nine Unknown were real and had been founded by the Indian Emperor Ashoka. They also claimed that Pope Silvester II had met them and that nineteenth-century French colonial administrator and writer Louis Jacolliot insisted on their existence.[2] The Nine Unknown were also the final dedicatees mentioned in the dedication of the first edition of Anton LaVey's Satanic Bible in 1969.[3]

The "Nine Unknown" have since been the subject of the several novels including Shadow Tyrants by Clive Cussler and Boyd Morrison; The Mahabharata Secret, a 2013 novel by Christopher C. Doyle; Finders, Keepers, a 2015 novel by Sapan Saxena; and Shobha Nihalani's Nine novel trilogy.[4]

The number nine is important in the American television series Heroes. Series writers and producers Aron Coliete and Joe Pakaski have credited the story of Ashoka and The Nine Unknown Men as one of the many influences for the series and as a clue to the mystery surrounding the number.

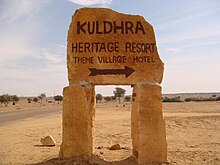

4. Cursed village of Kuldhara

Kuldhara Kuldhar | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Ruins of Kuldhara houses | |

Location of Kuldhara in Rajasthan, India | |

| Coordinates: 26.81°N 70.80°ECoordinates: 26.81°N 70.80°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Rajasthan |

| District | Jaisalmer |

| Elevation | 266 m (873 ft) |

Kuldhara is an abandoned village in the Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan, India. Established around the 13th century, it was once a prosperous village inhabited by Paliwal Brahmins. It was abandoned by the early 19th century for unknown reasons, possibly because of dwindling water supply, or as a local legend claims, because of persecution by the Jaisalmer State's minister Salim Singh. A 2017 study suggests that Kuldhara and other neighbouring villages were abandoned because of an earthquake.

Over years, Kuldhara acquired reputation as a haunted site, and the Government of Rajasthan decided to develop it as a tourist

Geography[edit]

The former village site is located about 18 km south-west of the Jaisalmer city. The village was located on an 861 m x 261 m rectangular site aligned in the north-south direction. The township was centred around a temple of the mother goddess. It had three longitudinal roads, which were cut through by a number of latitudinal narrow lanes.[1]

The remains of a city wall can be seen on the north and the south sides of the site. The eastern side of the town faces the dry-river bed of the small Kakni river. The western side was protected by the back-walls of man-made structures.

Establishment[edit]

The Kuldhara village was originally settled by Brahmins who had migrated from Pali to Jaisalmer region.[2] These migrants originating from Pali were called Paliwals. Tawarikh-i-Jaisalmer, an 1899 history book written by Lakshmi Chand, states that a Paliwal Brahmin named Kadhan was the first person to settle in the Kuldhara village. He excavated a pond called Udhansar in the village.[1]

The ruins of the village include 3 cremation grounds, with several devalis (memorial stones or cenotaphs).[3] The village was settled by the early 13th century, as indicated by two devali inscriptions. These inscriptions are dated in the Bhattik Samvat (a calendar era starting in 623 CE), and record the deaths of two residents in 1235 CE and 1238 CE respectively

Population[edit]

Ruins of 410 buildings can be seen in the former village.[1] Another 200 buildings were located in the lower township on the outskirts of the village.[5]

Lakshmi Chand's Tawarikh-i-Jaisalmer (1899) provides statistics about Paliwal population and households of several villages. Using the figure of 3.97 persons per household based on these statistics, and considering the number of ruined houses as 400, S. A. N. Rezavi estimated the 17th-18th century population of Kuldhara as 1,588. The British officer James Tod recorded the 1815 population of Kuldhara as 800 (in 200 households), based on information from "the best informed natives". By this time, the Paliwals had already started deserting the village. By 1890, the population of the village had declined to 37 people; the number of houses was recorded as 117.[6]

Social groups[edit]

There are several other devali inscriptions at the site. These inscriptions do not mention the term "Paliwal"; they only describe the inhabitants as Brahmin ("Vrahman" or "Vaman"). Several inscriptions mention the caste of the residents as "Kuldhar" or "Kaldhar". It appears that Kuldhara was a caste group among Paliwal Brahmins, and the village was named after this caste.[7]

Some inscriptions also mention the jati (sub-caste) and gotra (clan) of the residents. The various jatis mentioned in the inscriptions include Harjal, Harjalu, Harjaluni, Mudgal, Jisutiya, Loharthi, Lahthi, Lakhar, Saharan, Jag, Kalsar, and Mahajalar. The gotras mentioned include Asamar, Sutdhana, Gargvi and Gago. One inscription also mentions the kula (family lineage) of a Brahmin as Gonali. Apart from the Paliwal Brahmins, the inscriptions also mention two sutradhars (architects) named Dhanmag and Sujo Gopalna. The inscriptions indicate that the Brahmin residents married within the Brahmin community, although the jatis or sub-castes were exogamous.[7]

Culture[edit]

Religion[edit]

The residents of the village were Vaishnavites. The main temple of the village had sculptures of Vishnu and Mahishasura Mardini. Most of the inscriptions start with an invocation to Ganesha, whose miniature sculptures also appear on the gateways. The villagers also worshiped bull and a local horse-riding deity.[8]

Fashion[edit]

If the idols on the devalis are considered as representatives of the contemporary fashion, it appears that the men of Kuldhara wore Mughal-style turbans and jamas (tunic-like garment) with kamarband (a type of waist belt). They generally sported a beard, wore a necklace and carried a khanjar (dagger). The women wore tunics or lehengas, and some of them wore necklaces.[8]

Economy[edit]

The villagers were mostly agricultural traders, bankers and farmers. They used ornamented pottery made of fine clay.[5]

For agricultural purposes, the villagers used the water from the Kakni river and several wells. They also tapped the water using khareen, an artificial depression dammed on three sides. When the water in the khareen evaporated, it left soil conducive for growing jowar, wheat and gram. A 2.5 km2. khareen was situated to the south of Kuldhara.[9]

The Kakni river branches into two streams near Kuldhara. The first branch is called "Masurdi nadi"; the second branch is now a drain. The Kakni river is a seasonal river. When it went dry, the villagers tapped groundwater using wells and a step-wells. A pillar inscription states that Tejpal, a Kuldhara Brahmin, commissioned the step-well in 1815 VS (1757 CE).[10]

Decline[edit]

By the 19th century, the village had been deserted for unknown reasons. Possible causes proposed in the 20th century include lack of water and the atrocities of a Diwan (official) named Salim Singh (or Zalim Singh).[11]

By 1815, most of the wells in the village had dried up.[12] By 1850, only the step-well and two other deep wells were functional.[9] When S. A. N. Rezavi surveyed the village in the 1990s, the only water remaining at the site was the stagnant water at some portions of the dried-up river bed. The dwindling water supply would have greatly reduced agricultural productivity, without a corresponding reduction in tax demands from the Jaisalmer State. This could have forced the Paliwals to abandon Kuldhara.[12] A local legend claims that Salim Singh, the cruel minister of Jaisalmer, levied excessive taxes on the village, leading to its decline.[13]

As stated earlier, the historical records suggest that the population of the village declined gradually: its estimated population was around 1,588 during 17th-18th century; around 800 in 1815; and 37 in 1890.[6] However, a variation of the legend claims that the village was abandoned overnight. According to this version, the lecherous minister Salim Singh was attracted to a beautiful girl from the village. He sent his guards to force the villagers to hand over the girl. The villagers asked the guards to return next morning, and abandoned the village overnight.[14] Another version claims that 83 other villages in the area were also abandoned overnight.[15]

A 2017 study by A. B. Roy et al., published in Current Science, suggests that Kuldhara and other neighbouring Paliwal villages (such as Khabha) were destroyed because of an earthquake. According to the authors, the ruined houses in these villages show evidence of earthquake-related destruction, such as "collapsed roofs, fallen joists, lintels and pillars".[16] Such extensive destruction cannot be attributed to "the normal processes of weathering and erosion".[17] The authors further state that their theory is supported by "the evidence of recent tectonic activities and the observed ground movements along several major faults in the region".[18]

Tourism[edit]

The local legend claims that while deserting the village, the Paliwals imposed a curse that no one would be able to re-occupy the village. Those who tried to re-populate the village experienced paranormal activities, and therefore, the village remains uninhabited.[19]

Gradually, the village acquired reputation as a haunted place, and started attracting tourists.[20][21] The local residents around the area do not believe in the ghost stories, but propagate them in order to attract tourists.[22] In the early 2010s, Gaurav Tiwari of Indian Paranormal Society claimed to have observed paranormal activities at the site. The 18-member team of the Society along with 12 other people spent a night at the village. They claimed to have encountered moving shadows, haunting voices, talking spirits, and other paranormal activities.[23]

In 2006, the government set up a "Jurassic Cactus Park" at the site for botanical studies.[22] In 2011, some scenes of the movie Agent Vinod & In 2017 climax scenes of the Tamil Movie Theeran Adhigaaram Ondru were shot at the site. The film's crew raised new structures for their set. They painted the ruined walls with Taliban insignia and Urdu words for their shooting requirements. They also covered some of the walls with cow dung to get the rustic look. Many tourists accused them of defacing heritage property, and subsequently, the Rajasthan government stalled the shooting. The police booked cases against three of the crew members. The producers defended themselves blaming the episode on a misunderstanding, and stated that they believed they had the necessary permissions. The Archaeological department imposed a fine of ₹ 100,000 on the producers, and also asked them to deposit ₹ 300,000 for restoring the defaced structures. After three days of restoration, the Taliban pictures, the Urdu phrases and the cow dung was removed from the walls.[24][25]

In 2015, the Rajasthan government decided to actively develop the village as a tourist spot.[19] The project is being undertaken as a public-private partnership with Jindal Steel Works. The plan includes establishment of visitor facilities such as a cafe, a lounge, a folk-dance performance area, night-stay cottages and sho

5.Roopkund (locally known as Mystery Lake or Skeletons Lake)[1] is a high altitude glacial lake in the Uttarakhand state of India. It lies in the lap of Trishul massif. Located in the Himalayas, the area around the lake is uninhabited, and is roughly at an altitude of 16,470 feet (5,020 m),[1] surrounded by rock-strewn glaciers and snow-clad mountains. Roopkund is a popular trekking destination.[2]

With a depth of about 3 metres, Roopkund is widely known for the hundreds of ancient human skeletons found at the edge of the lake.[3] The human skeletal remains are visible at its bottom when the snow melts.[4] Research generally points to a semi-legendary event where a group of people were killed in a sudden, violent hailstorm in the 9th century.[5] Because of the human remains, the lake has been called Skeleton Lake in recent times

| Roopkund | |

|---|---|

| |

Lake in August 2014 | |

| Location | Chamoli, Uttarakhand |

| Coordinates | 30°15′44″N 79°43′54″ECoordinates: 30°15′44″N 79°43′54″E |

| Average depth | 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) |

| Surface elevation | 4,800 metres (15,700 ft |

Last months with the Indian National Army[edit]

During the last week of April 1945, Subhas Chandra Bose along with his senior Indian National Army (INA) officers, several hundred enlisted INA men, and nearly a hundred women from the INA's Rani of Jhansi Regiment left Rangoon by road for Moulmein in Burma.[8] Accompanied by Lieutenant General Saburo Isoda, the head of the Japanese-INA liaison organization Hikari Kikan, their Japanese military convoy was able to reach the right bank of the Sittang river, albeit slowly.[9] (See map 1.) However, very few vehicles were able to cross the river because of American strafing runs. Bose and his party walked the remaining 80 miles (130 km) to Moulmein over the next week.[9] Moulmein then was the terminus of the Death Railway, constructed earlier by British, Australian, and Dutch prisoners of war, linking Burma to Siam (now Thailand).[9] At Moulmein, Bose's group was also joined by 500 men from the X-regiment, INA's first guerrilla regiment, who arrived from a different location in Lower Burma.[10]

A year and a half earlier, 16,000 INA men and 100 women had entered Burma from Malaya.[10] Now, less than one tenth that number left the country, arriving in Bangkok during the first week of May.[10] The remaining nine tenths were either killed in action, died from malnutrition or injuries after the battles of Imphal and Kohima. Others were captured by the British, turned themselves in, or simply disappeared.[10] Bose stayed in Bangkok for a month, where soon after his arrival he heard the news of Germany's surrender on May 8.[11] Bose spent the next two months between June and July 1945 in Singapore,[11] and in both places attempted to raise funds for billeting his soldiers or rehabilitating them if they chose to return to civilian life, which most of the women did.[12] In his nightly radio broadcasts, Bose spoke with increasing virulence against Gandhi, who had been released from jail in 1944, and was engaged in talks with British administrators, envoys and Muslim League leaders.[13] Some senior INA officers began to feel frustrated or disillusioned with Bose and to prepare quietly for the arrival of the British and its consequences.[13]

During the first two weeks of August 1945, events began to unfold rapidly. With the British threatening to invade Malaya and with daily American aerial bombings, Bose's presence in Singapore became riskier by the day. His chief of staff J. R. Bhonsle suggested that he prepare to leave Singapore.[14] On 3 August 1945, Bose received a cable from General Isoda advising him to urgently evacuate to Saigon in Japanese-controlled French Indochina (now Vietnam).[14] On 10 August, Bose learnt that the Soviet Union had entered the war and invaded Manchuria. At the same time he heard about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[15] Finally, on 16 August, after being informed of the unconditional surrender of Japan, Bose decided to leave for Saigon along with a handful of his aides.[14]

Last days and journeys[edit]

Reliable strands of historical narrative about Bose's last days are united up to this point. However, they separate briefly for the period between 16 August, when Bose received news of Japan's surrender in Singapore, and shortly after noon on 17 August, when Bose and his party arrived at Saigon airport from Saigon city to board a plane.[16] (See map 2.)

In one version, Bose flew out from Singapore to Saigon, stopping briefly in Bangkok, on the 16th. Soon after arriving in Saigon, he visited Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, head of the Japanese forces in Southeast Asia, and requested him to arrange a flight to the Soviet Union.[14] Although until the day before, the Soviet Union had been a belligerent of Japan, it was also seen, at least by Bose, as increasingly anti-British,[17] and, consequently, a possible base of his future operations against the British Raj.[14] Terauchi, in turn, cabled Japan's Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) in Tokyo for permission, which was quickly denied.[14] In the words of historian Joyce Chapman Lebra, the IGHQ felt that it "would be unfair of Bose to write off Japan and go over to Soviet Union after receiving so much help from Japan. Terauchi added in talking with Bose that it would be unreasonable for him to take a step which was opposed by the Japanese."[14] Privately, however, Terauchi still felt sympathy for Bose—one that had been formed during their two-year-long association.[14] He somehow managed to arrange room for Bose on a flight leaving Saigon on the morning of 17 August 1945 bound for Tokyo, but stopping en route in Dairen, Manchuria—which was still Japanese-occupied, but toward which the Soviet army was fast approaching—where Bose was to have disembarked and to have awaited his fate at the hand of the Soviets.[14]

In another version, Bose left Singapore with his party on the 16th and stopped en route in Bangkok, surprising INA officer in-charge there, J. R. Bhonsle, who quickly made arrangements for Bose's overnight stay.[16] Word of Bose's arrival, however, got out, and soon local members of the Indian Independence League (IIL), the INA, and the Thai Indian business community turned up at the hotel.[16] According to historian Peter Ward Fay, Bose "sat up half the night holding court—and in the morning flew on to Saigon, this time accompanied by General Isoda ..."[16] Arriving in Saigon, late in the morning, there was little time to visit Field Marshal Terauchi, who was in Dalat in the Central Highlands of French Indo-China, an hour away by plane.[16] Consequently, Isoda himself, without consulting with higher ups, arranged room for Bose on a flight leaving around noon.[16]

In the third sketchier version, Bose left Singapore on the 17th.[17] According to historian Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper, "On 17 August he issued a final order of the day, dissolving the INA with the words, 'The roads to Delhi are many and Delhi still remains our goal.' He then flew out to China via French Indo-China. If all else failed he wanted to become a prisoner of the Soviets: 'They are the only ones who will resist the British. My fate is with them'."[17]

Around noon on 17 August, the strands again reunite. At Saigon airport, a Mitsubishi Ki-21 heavy bomber, of the type code named Sally by the Allies, was waiting for Bose and his party.[18][19] In addition to Bose, the INA group comprised Colonel Habibur Rahman, his secretary; S. A. Ayer, a member of his cabinet; Major Abid Hasan, his old associate who had made the hazardous submarine journey from Germany to Sumatra in 1943; and three others.[18] To their dismay, they learned upon arrival that there was room for only one INA passenger.[19] Bose complained, and the beleaguered General Isoda gave in and hurriedly arranged for a second seat.[19] Bose chose Habibur Rahman to accompany him.[19] It was understood that the others in the INA party would follow him on later flights. There was further delay at Saigon airport. According to historian Joyce Chapman Lebra, "a gift of treasure contributed by local Indians was presented to Bose as he was about to board the plane. The two heavy strong-boxes added overweight to the plane's full load."[18] Sometime between noon and 2 PM, the twin-engine plane took off with 12 or 13 people aboard: a crew of three or four, a group of Japanese army and air force officers, including Lieutenant-General Tsunamasa Shidei, the Vice Chief of Staff of the Japanese Kwantung Army, which although fast retreating in Manchuria still held the Manchurian peninsula, and Bose and Rahman. Bose was sitting a little to the rear of the portside wing;[18] the bomber, under normal circumstances, carried a crew of five.

That these flights were possible a few days after Japan's surrender was the result of a lack of clarity about what had occurred. Although Japan had unconditionally surrendered, when Emperor Hirohito had made his announcement over the radio, he had used formal Japanese, not entirely intelligible to ordinary people and, instead of using the word "surrender" (in Japanese), had mentioned only "abiding by the terms of the Potsdam Declaration." Consequently, many people, especially in Japanese-occupied territories, were unsure if anything had significantly changed, allowing a window of a few days for the Japanese air force to continue flying. Although the Japanese and Bose were tight lipped about the destination of the bomber, it was widely assumed by Bose's staff left behind on the tarmac in Saigon that the plane was bound for Dairen on the Manchurian peninsula, which, as stated above, was still under Japanese control. Bose had been talking for over a year about the importance of making contact with the communists, both Russian and Chinese. In 1944, he had asked a minister in his cabinet, Anand Mohan Sahay to travel to Tokyo for the purposes of making contact with the Soviet ambassador, Jacob Malik.[18] However, after consulting the Japanese foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, Sahay decided against it.[18] In May 1945, Sahay had again written to Shigemitsu requesting him to contact Soviet authorities on behalf of Bose; again the reply had been in the negative.[18] Bose had been continually querying General Isoda for over a year about the Japanese army's readiness in Manchuria.[18] After the war, the Japanese confirmed to the British investigators and later Indian commissions of inquiry, that plane was indeed bound for Dairen, and that fellow passenger General Shidea of the Kwantung Army, was to have disembarked with Bose in Dairen and to have served as the main liaison and negotiator for Bose's transfer into Soviet controlled territory in Manchuria.[18][17]

The plane had flown north. By the time it was near the northern coast of French Indo-China, darkness had begun to close in, and the pilot decided to make an unscheduled stop in Tourane (now Da Nang, Vietnam).[20] The passengers stayed overnight at a hotel, and the crew, worried that the plane was overloaded, shed some 500 pounds of equipment and luggage, and also refueled the plane.[20] Before dawn the next morning, the group flew out again, this time east to Taihoku, Formosa (now Taipei, Taiwan), which was a scheduled stop, arriving there around noon on 18 August 1945.[20] During the two-hour stop in Taihoku, the plane was again refueled, while the passengers ate lunch.[20] The chief pilot and the ground engineer, and Major Kono, seemed concerned about the portside engine, and, once all the passengers were on board, the engine was tested by repeatedly throttling up and down.[20][21] The concerns allayed, the plane finally took off, in different accounts, as early as 2 PM,[20] and as late as 2:30 PM,[21][22] watched by ground engineers.[20]

Death in plane crash[edit]

Just as the bomber was leaving the standard path taken by aircraft during take-off, the passengers inside heard a loud sound, similar to an engine backfiring.[21][22] The mechanics on the tarmac saw something fall out of the plane.[20] It was the portside engine, or a part of it, and the propeller.[20][21] The plane swung wildly to the right and plummeted, crashing, breaking into two, and exploding into flames.[20][21] Inside, the chief pilot, copilot and General Shidea were instantly killed.[20][23] Rahman was stunned, passing out briefly, and Bose, although conscious and not fatally hurt, was soaked in gasoline.[20] When Rahman came to, he and Bose attempted to leave by the rear door but found it blocked by the luggage.[23] They then decided to run through the flames and exit from the front.[23] The ground staff, now approaching the plane, saw two people staggering towards them, one of whom had become a human torch.[20] The human torch turned out to be Bose, whose gasoline-soaked clothes had instantly ignited.[23] Rahman and a few others managed to smother the flames, but also noticed that Bose's face and head appeared badly burned.[23] According to Joyce Chapman Lebra, "A truck which served as ambulance rushed Bose and the other passengers to the Nanmon Military Hospital south of Taihoku."[20] The airport personnel called Dr. Taneyoshi Yoshimi, the surgeon-in-charge at the hospital at around 3 PM.[23] Bose was conscious and mostly coherent when they reached the hospital, and for some time thereafter.[24] Bose was naked, except for a blanket wrapped around him, and Dr. Yoshimi immediately saw evidence of third-degree burns on many parts of the body, especially on his chest, doubting very much that he would live.[24] Dr. Yoshimi promptly began to treat Bose and was assisted by Dr. Tsuruta.[24] According to historian Leonard A. Gordon, who interviewed all the hospital personnel later:

Soon, in spite of the treatment, Bose went into a coma.[25][20] He died a few hours later, between 9 and 10 PM.[25][20]

Bose's body was cremated in the main Taihoku crematorium two days later, 20 August 1945.[26] On 23 August 1945, the Japanese news agency Domei announced the death of Bose and Shidea.[20] On 7 September a Japanese officer, Lieutenant Tatsuo Hayashida, carried Bose's ashes to Tokyo, and the following morning they were handed to the president of the Tokyo Indian Independence League, Rama Murti.[27] On 14 September a memorial service was held for Bose in Tokyo and a few days later the ashes were turned over to the priest of the Renkōji Temple of Nichiren Buddhism in Tokyo.[28][29] There they have remained ever since.[29]

Among the INA personnel, there was widespread disbelief, shock, and trauma. Most affected were the young Tamil Indians from Malaya and Singapore, men and women, who comprised the bulk of the civilians who had enlisted in the INA.[17] The professional soldiers in the INA, most of whom were Punjabis, faced an uncertain future, with many fatalistically expecting reprisals from the British.[17] In India the Indian National Congress's official line was succinctly expressed in a letter Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi wrote to Rajkumari Amrit Kaur.[17] Said Gandhi, "Subhas Bose has died well. He was undoubtedly a patriot, though misguided."[17] Many congressmen had not forgiven Bose for quarreling with Gandhi and for collaborating with what they considered was Japanese fascism.[17] The Indian soldiers in the British Indian army, some two and a half million of whom had fought during the Second World War, were conflicted about the INA. Some saw the INA as traitors and wanted them punished; others felt more sympathetic. The British Raj, though never seriously threatened by the INA, was to try 300 INA officers for treason in the INA trials, but was to eventually backtrack in the face of its own end.[17]

Legends of Bose's survival[edit]

Immediate post-war legends[edit]

Subhas Chandra Bose's exploits had become legendary long before his physical death in August 1945.[30][h] From the time he had escaped house arrest in Calcutta in 1940, rumours had been rife in India about whether or not he was alive, and if the latter, where he was and what he was doing.[30] His appearance in faraway Germany in 1941 created a sense of mystery about his activities. With Congress leaders in jail in the wake of the Quit India Resolution in August 1942 and the Indian public starved for political news, Bose's radio broadcasts from Berlin charting radical plans for India's liberation during a time when the star of Germany was still rising and that of Britain was at its lowest, made him an object of adulation among many in India and southeast Asia.[31] During his two years in Germany, according to historian Romain Hayes, "If Bose gradually obtained respect in Berlin, in Tokyo he earned fervent admiration and was seen very much as an 'Indian samurai'."[32] Thus it was that when Bose appeared in Southeast Asia in July 1943, brought mysteriously on German and Japanese submarines, he was already a figure of mythical size and reach.[31]

After Bose's death, Bose's other lieutenants, who were to have accompanied him to Manchuria, but were left behind on the tarmac in Saigon, never saw a body.[33] There were no photographs taken of the injured or deceased Bose, neither was a death certificate issued.[33] According to historian Leonard A. Gordon,

For these two reasons, when news of Bose's death was reported, many in the INA refused to believe it and were able to transmit their disbelief to a wider public.[4] The source of the widespread skepticism in the INA might have been Bose's senior officer J. R. Bhonsle.[4] Bhonsle, unlike some other senior officers, had been kept in the dark about Bose's final plans, in part because he had also become an agent for the British. When a Japanese delegation, which included General Isoda, visited Bhonsle on 19 August 1945 to break the news and offer condolences, he responded by telling Isoda that Bose had not died, rather his disappearance has been covered up.[4] Even Mohandas Gandhi swiftly said that he was skeptical about the air crash, but changed his mind after meeting the Indian survivor Habibur Rahman.[34] As in 1940, before long, in 1945, rumours were rife about what had happened to Bose, whether he was in Soviet-held Manchuria, a prisoner of the Soviet army, or whether he had gone into hiding with the cooperation of the Soviet army.[4] Lakshmi Swaminathan, of the all-female Rani of Jhansi regiment of the INA, later Lakshmi Sahgal, said in spring 1946 that she thought Bose was in China.[34] Many rumours spoke of Bose preparing for his final march on Delhi.[4] This was the time when Bose began to be sighted by people, one sighter claiming "he had met Bose in a third-class compartment of the Bombay express on a Thursday."[34]

Enduring legends[edit]

In the 1950s, stories appeared in which Bose had become a sadhu, or Hindu renunciant. The best-known and most intricate of the renunciant tales of Subhas Bose, and one which, according to historian Leonard A. Gordon, may "properly be called a myth," was told in the early 1960s.[35] Some associates of Bose, from two decades before, had formed an organization, the "Subhasbadi Janata", to promote this story in which Bose was now the chief sadhu of an ashram (or hermitage) in Shaulmari (also Shoulmari) in North Bengal.[35] The Janata brought out published material, including several newspapers and magazines. Of these, some were long lived and some short, but all, by their number, attempted to create the illusion of the story's newsworthiness.[35] The chief sadhu himself vigorously denied being Bose.[36] Several intimates of Bose, including some politicians, who met with the sadhu, supported the denials.[36] Even so, the Subhasbadi Janata was able to create an elaborate chronology of Bose's post-war activities.[36]

According to this chronology, after his return to India, Bose returned to the vocation of his youth: he became a Hindu renunciant.[36] He attended unseen Gandhi's cremation in Delhi in early February 1948; walked across and around India several times; became a yogi at a Shiva temple in Bareilly in north central India from 1956 to 1959; became a practitioner of herbal medicine and effected several cures, including one of tuberculosis; and established the Shaulmari Ashram in 1959, taking the religious name Srimat Saradanandaji.[nb 1][36] Bose, moreover, was engaged in tapasya, or meditation, to free the world, his goals having been broadened, after his first goal—freeing India—was achieved.[37] His attempt to do so, however, and to assume his true identity, was being thwarted jointly by political parties, newspapers, the Indian government, even foreign governments.[37]

Others stories appeared, spun by the Janata and by others.[38] Bose was still in the Soviet Union or the People's Republic of China; attended the Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru's cremation in 1964, but, this time, neglecting to disallow a Janata-published newspaper to photograph him; and gave notice to the Janata of his return to Calcutta, for which several much publicized rallies were organized.[38] Bose did not appear.[38] The Janata eventually broke up, its reputation marred by successive non-appearances of its protagonist.[38] The real sadhu of Shaulmari, who continued to deny he was Bose, died in 1977.[38] It was also claimed that Nikita Khrushchev had reportedly told an interpreter during his New Delhi visit that Bose can be produced within 45 days if Nehru wishes.[39]

Still other stories or hoaxes—elucidated with conspiracies and accompanied with fake photographs—of the now-aging Bose being in the Soviet Union or China had traction well into the early 80s.[38] Bose was seen in a photograph taken in Beijing, inexplicably parading with the Chinese Red Army.[38] Bose was said to be in a Soviet Gulag. The Soviet leadership was said to be blackmailing Nehru, and later, Indira Gandhi, with the threat of releasing Bose.[40] An Indian member of parliament, Samar Guha, released in 1979 what he claimed was a contemporaneous photograph of Bose. This turned out to have been doctored, comprising one-half Bose and one-half his elder brother Sarat Chandra Bose.[41] Guha also charged Nehru with having had knowledge of Bose's incarceration in the Soviet Union even in the 1950s, a charge Guha recanted after he was sued.[41]

For the remainder of the century and into the next, the renunciant legends continued to appear. Most prominently, a retired judge, who had been appointed by the Indian Government in 1999 to undertake an enquiry into Bose's death, brought public notice to another sannyasi or renunciant, "Gumnami Baba,"[nb 2] also known by his religious name, "Bhagwanji,"[nb 3] who was said to have lived in the town of Faizabad in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.[42] According to historian Sugata Bose,

Earlier, in 1977, summing up the extant Bose legends, historian Joyce Chapman Lebra had written,

Perspectives on durability of legends[edit]

According to historians Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper:

Amid all this, Joyce Chapman Lebra,[44] wrote in 2008:

Inquiries[edit]

Figgess Report 1946[edit]

Confronted with rumours about Bose, which had begun to spread within days of his death, the Supreme Allied Command, South-east Asia, under Mountbatten, tasked Colonel (later Sir) John Figgess, an intelligence officer, with investigating Bose's death.[33] Figgess's report, submitted on 25 July 1946, however, was confidential, being work done in Indian Political Intelligence (IPI), a partially secret branch of the Government of India.[33] Figgess was interviewed in the 1980s by Leonard A. Gordon and confirmed writing the report.[33] In 1997, the British Government made most of the IPI files available for public viewing in the India Office Records of the British Library.[33] However, the Figgess report was not among them. A photocopy of the Figess report was soon anonymously donated for public viewing to the British Library in the European manuscripts collection, as Eur. MSS. c 785.[45] Good candidates for the donor, according to Leonard Gordon, are Figgess himself, who had died in 1997, or more likely another British intelligence officer in wartime India, Hugh Toye, the author of a book (Toye 1959).[45]

The crucial paragraph in the Figgess report (by Colonel John Figgess, Indian Political Intelligence, 25 July 1946,) is:[45]

The remaining four pages of the Figgess report contain interviews with two survivors of the plane crash, Lt. Cols. Nonogaki and Sakai, with Dr. Yoshimi, who treated Bose in the hospital and with others involved in post-death arrangements.[45] In 1979, Leonard Gordon himself interviewed "Lt. Cols. Nonogaki and Sakai, and, (in addition, plane-crash survivor) Major Kono; Dr. Yoshimi ...; the Japanese orderly who sat in the room through these treatments; and the Japanese officer, Lt. Hayashita, who carried Bose's ashes from the crematorium in Taipei to Japan."[45]

The Figgess report and Leonard Gordon's investigations confirm four facts:

- The crash near Taihoku airport on 18 August 1945 of a plane on which Subhas Chandra Bose was a passenger;

- Bose's death in the nearby military hospital on the same day;

- Bose's cremation in Taihoku; and

- transfer of Bose's ashes to Tokyo.[45]

Shah Nawaz Committee 1956[edit]

With the goal of quelling the rumours about what happened to Subhas Chandra Bose after mid-August 1945, the Government of India in 1956 appointed a three-man committee headed by Shah Nawaz Khan.[34][28] Khan was at the time a Member of Parliament as well as a former Lieutenant Colonel in the Indian National Army and the best-known defendant in the INA Trials of a decade before.[34][28] The other members of the committee were S. N. Maitra, ICS, who was nominated by the Government of West Bengal, and Suresh Chandra Bose, an elder brother of Bose.[34][28] The committee is referred to as the "Shah Nawaj Committee" or the "Netaji Inquiry Committee."[34]

From April to July 1956, the committee interviewed 67 witnesses in India, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam.[34][28] In particular, the committee interviewed all the survivors of the plane crash, some of whom had scars on their bodies from burns.[34] The committee interviewed Dr. Yoshimi, the surgeon at the Taihoku Military Hospital who treated Bose in his last hours.[34] It also interviewed Bose's Indian companion on the flight, Habib ur Rahman, who, after the partition, had moved to Pakistan and had burn scars from the plane crash.[34] Although there were minor discrepancies here and there in the evidence, the first two members of the committee, Khan and Maitra, concluded that Bose had died in the plane crash in Taihoku on 18 August 1945.[34][28]

Bose's brother, Suresh Chandra Bose, however, after having signed off on the initial conclusions, declined to sign the final report.[34] He, moreover, wrote a dissenting note in which he claimed that the other members and staff of the Shah Nawaz Committee had deliberately withheld some crucial evidence from him, that the committee had been directed by Jawaharlal Nehru to infer death by plane crash, and that the other committee members, along with Bengal's chief minister B. C. Roy, had pressured him bluntly to sign the conclusions of their final report.[34][28]

According to historian Leonard A. Gordon,[34]

Khosla Commission 1970[edit]

In 1977, two decades after the Shah Nawaz committee had reported its findings, historian Joyce Chapman Lebra wrote about Suresh Chandra Bose's dissenting note: "Whatever Mr Bose's motives in issuing his minority report, he has helped to perpetuate until the present the faith that Subhas Chandra Bose still lives."[28] In fact, during the early 1960s, the rumours about Subhas Bose's extant forms only increased.[35]

In 1970, the Government of India appointed a new commission to enquire into the "disappearance" of Bose.[35] With a view to heading off more minority reports, this time it was a "one-man commission."[35] The single investigator was G. D. Khosla, a retired chief justice of the Punjab High Court.[35] As Justice Khosla had other duties, he submitted his report only in 1974.[35]

Justice Khosla, who brought his legal background to bear on the issue in a methodical fashion,[46] not only concurred with the earlier reports of Figess and the Shah Nawaz Committee on the main facts of Bose's death,[46] but also evaluated the alternative explanations of Bose's disappearance and the motives of those promoting stories of Netaji sightings.[35] Historian Leonard A. Gordon writes:

Mukherjee Commission 2005[edit]

In 1999, following a court order, the Indian government appointed retired Supreme Court judge Manoj Kumar Mukherjee to probe the death of Bose. The commission perused hundreds of files on Bose's death drawn from several countries and visited Japan, Russia and Taiwan. Although oral accounts were in favour of the plane crash, the commission concluded that those accounts could not be relied upon and that there was a secret plan to ensure Bose's safe passage to the USSR with the knowledge of Japanese authorities and Habibur Rahman. It though failed to make any progress about Bose's activities, after the staged crash.[47] The commission also concluded that the ashes kept at the Renkoji temple (which supposedly contain skeletal remains) reported to be Bose's, were of Ichiro Okura, a Japanese soldier who died of cardiac arrest[48] but asked for a DNA test.[49] It also determined Gumnami Baba to be different from Subhas Bose in light of a DNA profiling test.[50][51]

The Mukherjee Commission submitted its report to on 8 November 2005 after 3 extensions and it was tabled in the Indian Parliament on 17 May 2006. The Indian Government rejected the findings of the commission.[48]

Key findings of the report (esp. about their rejection of the plane-crash-theory) have been criticized[49][51] and the report contains other glaring inaccuracies.[49][47] Sugata Bose notes that Mukherjee himself admitted to harbouring a preconceived notion about Bose being alive and living as an ascetic. He also blames the commission for entertaining the most preposterous and fanciful of all stories, thus adding to the confusion and for failing to distinguish between the highly probable and utterly impossible.[51] Gordon notes that the report had failed to list all of the people who were interviewed by the committee (including him) and that it mis-listed and mis-titled many of the books, used as sources.[52]

Japanese government report 1956, declassified September 2016[edit]

An investigative report by Japanese government titled "Investigation on the cause of death and other matters of the late Subhas Chandra Bose" was declassified on 1 September 2016. It concluded that Bose died in a plane crash in Taiwan on 18 August 1945. The report was completed in January 1956 and was handed over to the Indian embassy in Tokyo, but was not made public for more than 60 years as it was classified. According to the report, just after takeoff a propellor blade on the airplane in which Bose was traveling broke off and the engine fell off the plane, which then crashed and burst into flames. When Bose exited it his clothes caught fire and he was severely burned. He was admitted to hospital, and although he was conscious and able to carry on a conversation for some time he died several hours later

No comments:

Post a Comment

if you have any doubts.please let me know